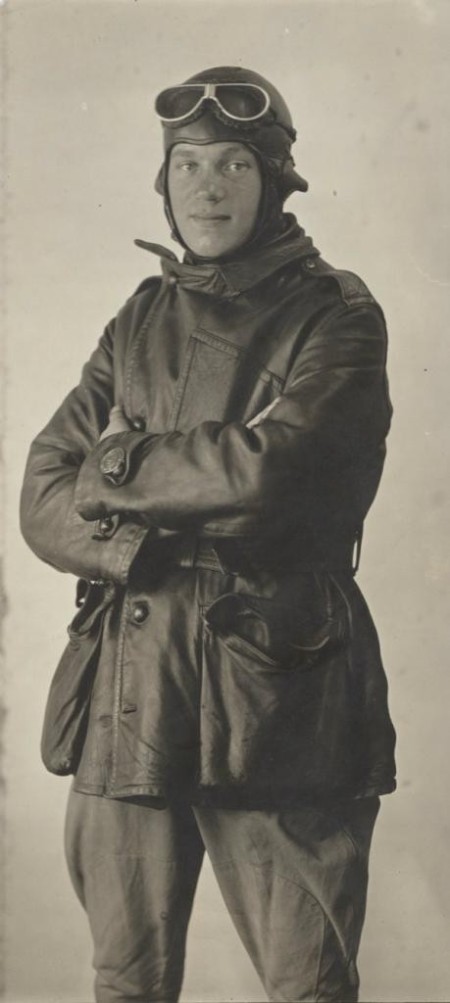

Maj. Rueben Fleet was in charge of pilot training for the U.S. Army when he was given nine days to establish flying operations for the Post Office Department. He is shown here after having just flown in to Potomac Park on the morning of the inaugural flight. Note the road map tied to his leg. Also note the proximity of the trees to the landing field.

Lt. James Edgerton and his sister celebrate his successful, first airmail flight into Washington, D.C. on May 15, 1918. Edgerton, who was named to the team because his father was purchasing agent for the post office, eventually flew more miles than any other Army airmail pilot. In 1919, he became the youngest federal executive in the U.S. government when he was named chief of flying operations for the Post Office Department.

At 25 years of age, the tall, blond blue-eyed Norwegian-born Max Miller earned $3,600 a years as the first civilian airmail pilots hired by the Post Office Department. He died 1920 when the all-metal Junkers he was flying caught fire and crashed. Witnesses said they saw Miller throwing bags of mail out the window as the airplane plummeted to the ground.

A former race car driver, Eddie “Turk Bird” Gardner, named so because his plane wobbled like a turkey on takeoffs and landings, was one of the old men of airmail at the age of 30.

It wasn’t a man who first flew the mail between Chicago and New York. It was Katherine Stinson, who piloted the route for the Post Office Department three months before the Pathfinder flights of Max Miller and Eddie Gardner. Stinson was the fourth woman in the U.S. to earn a pilot’s license, and in 1917 became the first woman to fly in the Orient.

It was E. Hamilton Lee, known as Ham, who taught Jack Knight to fly as an Army instructor at Ellington Field in Texas. With an ever-present cigar in his mouth, the dapper Lee flew out of almost every major airfield operated by the Post Office Department.

Nicknamed “Sky” by his parents, the skinny Jack Knight from Buchanan, Michigan, was born to fly. He spent thousands of hours flying the mail from the cockpit of a de Havilland DH-4.

Bundled up for winter weather, Jack Knight stands by in his cockpit to fly another stage in the February 1921 transcontinental run that would include the airmail’s first-ever night flight. People on the ground lit bonfires along the route so the pilot would be able to find his way through the night. The cross-country relay from New York to San Francisco took only about 33 hours, beating the fastest train train by 65 hours, and, in the process, saving the U.S. Air Mail Service.

Mavericks of the Sky draws on exhaustive research of new archival material to bring forward this unforgettable story of adventure, heroism and suspense set against the threshold of the Jazz Age. It was a dangerous time for mail pilots; fully one-quarter of the pilots died while trying to push the limits of flight to the extreme. Yet, still they signed on in droves—these ex-barnstormers, racecar drivers and WWI flying aces who willingly risked their lives in order to continue their obsession with flying.

Nicknamed “The Suicide Club,” the men of the U.S. Air Mail Service were an amalgam of brazen, headstrong aviators bent on defying the odds. Climbing into their flimsy wood and cloth-covered biplanes they moved the mail through torrential rain and blinding snowstorms, relying on their wits and instincts to keep them out of trouble.

They were constantly driven by tough-talking Second Assistant Postmaster General Otto Praeger—a gritty newspaperman who along with his boss Albert Burleson, the tenacious postmaster general in the cabinet of President Woodrow Wilson, held a common faith in the future of aviation.

Despite the deaths, the public skepticism and the contempt in which Congress held airmail, Praeger and Burleson refused to give up. Day after day, they held to the same impossible conviction—that airmail could be reliable and eventually far superior to rail service. To prove their point, mail pilots were ordered to maintain strict timetables through the cruelest of weather conditions, creating a bitter clash of wills between postal officials and the group-proud pilots who chafed under their vice-like dictums and policies.

Yet together, this battling group of visionaries left behind an undeniable legacy, both to modern aviation and to the world. Just three years after the first inaugural flight, the U.S. Post Office Department succeeded in expanding airmail westward, ultimately connecting the entire county by air, from New York to San Francisco, establishing the first reliable application of powered flight for civilian use.

Rosenberg and Macaulay unfold the lives and exploits of these unlikely American heroes in a narrative that is as irresistibly fascinating as its subject—revealing the underpinnings of the American pioneer spirit.

Hardcover published by William Morrow, paperback published by Harper Perennial, with Kindle version also available.